Watching Stuart get out of his electrician’s van was excruciating. Sl-o-o-o-w-ly his ponderous gray head emerged. Slo-o-o-w-ly he set one foot on the ground and slo-o-o-w-ly followed it with the other. Slo-o-o-w-ly he turned his heavy body on his cane. Slo-o-o-w-ly stepped toward the back of his truck and opened the door to a wild jumble of transformers and conduits and circuit tracers and stack switches. He had everything, and only he knew how he was able, amidst the jumble, to find anything. Dad liked Stuart because he was of the old school and knew what he was doing, his prices were reasonable, and he kept on hand outdated parts no longer available anywhere else. He could patch up Dad’s outdated pump and milk tank and wiring system and keep him going another year at minimal cost. To a small farmer struggling with rising costs and lowering milk prices, that is important.

With eighty odd years behind them, Stuart’s fingers were stiff-jointed and uncooperative, protesting, I suppose, for union rights and a proper retirement. Stuart’s brain, being sturdy and unassuming−as is all true intelligence−had no thought of union rights and served Stuart competently until the day of his death. But that is getting ahead of my story.

First, there was Edna.

A neighbor found her wandering down the road one day, with no idea of where she was going, and reported it to social services. “Unsafe,” they said. “Unfit. Run-down trailer, no handicap access, cans and cat pee everywhere. It’s neglect.”

There was a court case, and Edna was taken to the nearest nursing home. If Stuart wanted her back, the state ruled, he would have to provide home care and a trailer with handicap access. And Stuart wanted her back. They had married in their forties, a first for both of them, she an English teacher and he an electrician. They never had any children, but they both loved animals. They accumulated cats.

Stuart pulled in a new, handicap-accessible trailer next to the old and moved himself and brought Edna home again. He also brought the cats. Five or six, maybe. About the same number of the more independent stayed in the old trailer, where they had the free run of the place. Stuart trudged across the yard every day to feed them, beating a path through the snow. The floor of the place was covered ankle deep in cat food tins and smelled overwhelmingly of cat urine and cat feces and cat whatever-it-is-they-spit-from-their-mouths-with-weird-gut-wrenching-coughs.

It was about this time my sister Dora and I came on the scene. Stuart had succeeded in hiring help for the weekdays, but he needed someone to cover Saturdays. Dad, being an old friend, wanted to help him out and volunteered his daughters. “If you take turns, it’s only every other Saturday,” he said. “And it’s a good job. He pays $11 an hour.” This was in the years when minimum hovered around $6 an hour. Stuart was a generous man.

I was eighteen and just out of high school when I started working for Stuart, and I kept the job for three years. When Edna began to need full-time care, Dora and I went from working every other Saturday to working the night shift. We watched Edna digress in a short time from a pleasant but forgetful lady to a silent invalid. Stuart was honor-bound to keep her out of the nursing home, but looking back, I wonder if she wouldn’t have been better off there. Stuart hired, for the most part, unskilled workers. One girl called in or came in late almost every morning and, in her off hours, served jail time for drunk driving. Another girl stole from him. And Edna spent long hours just sitting, watching television−though it is doubtful she comprehended it−or listening to music. In a nursing home, at least there would have been a Social Worker and Activities.

But who can blame him for wanting her home? He believed nursing home care would be inferior, that she would become just another number. At home, at least, she was in a familiar environment and received one-on-one care. And probably he was right.

Dora and I learned everything we needed to know about aide work right on the job. We learned to change incontinence pads, to reposition Edna’s immobile body, to flush her feeding tube with water, to transport her from the bed to the recliner with a mechanical lift. We slept on the couch close to Edna’s hospital bed and woke every so often to check on her. The job was easy, but not pleasant. The place reeked of cat urine, and I would wake in the night to a snarling cat tiff or a cat crouched against the wall, spitting up hairballs. Stuart slept at the back of the trailer and, late in the mornings, brought his ponderous body out to the kitchen for a bowl of cold cereal. He sat at his mail-strewn table to eat, and one particular long-haired, peach-colored cat would sprawl his body companionably across the table, right next to Stuart’s bowl.

After breakfast, when Stuart was able to pull himself together−which time grew longer and longer as the months progressed−he would go out. Sometimes on a job with his friendly and competent assistant. Sometimes he went only to feed the cats at the third cat haven which he owned, a beaten-down farmhouse several miles away. Five or six cats lived there, serving no other purpose than to give Stuart something to do. He wanted to die in his boots, he said.

For Edna, it seemed death was imminent. Hospice predicted not more than a couple months, but that time stretched into years. She was taken by ambulance to the hospital several times, but each time ended up at home again, ready for another round in her empty shell of a life. Every night, on his way to his bed at the back of the trailer, Stuart would stop by her bed. “Good night, Edna,” he would say. “I love you.” She never responded or acknowledged him in any way, her brain too far deteriorated to register a relationship. At least, that’s what I thought. It seemed pointless, really, for him to even try.

Stuart got slower and slower, and one day, he died. Edna, who had been holding on against expectations all this time, died a week after he did.

And I had thought she didn’t know the difference.

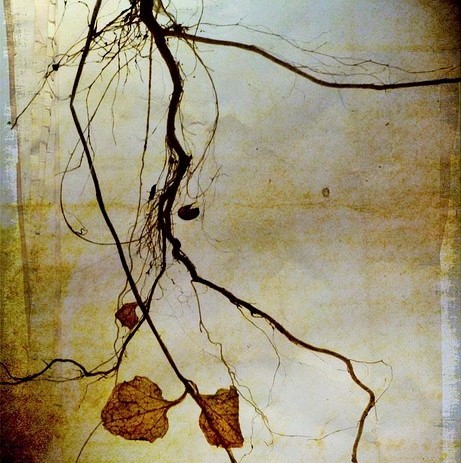

Love is, at its beginnings, a new-grown leaf, a budding flower, a delectable fruit. At its end it is only a gnarled root.

Edna was buried in early March. The cats went to the animal shelter.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Since writing this post, I’ve learned a few more details. To hear the rest of the story, read my next post, The Unknown Facts of Stuart and Edna’s Love Story.”

Awww. A beautiful story. Tears….

That is love through thick or thin!

Pingback: The Unknown Facts of Stuart and Edna's Love Story | Properties of Light