Since we lost our small one (you can read that post here), I have been thinking a lot more about Charlene, my darling little old lady friend who died. I like to picture the two of them together somewhere in a place I can’t quite get my mind around–but that doesn’t matter as much as the fact that I want them to be together. I’ve asked Jesus to introduce the two of them. I know that sounds silly, because probably in that place you need no introductions–but it made me feel better to ask.

Since we lost our small one (you can read that post here), I have been thinking a lot more about Charlene, my darling little old lady friend who died. I like to picture the two of them together somewhere in a place I can’t quite get my mind around–but that doesn’t matter as much as the fact that I want them to be together. I’ve asked Jesus to introduce the two of them. I know that sounds silly, because probably in that place you need no introductions–but it made me feel better to ask.

I used to write about her now and then on this blog, and today I’d like to share a post about our friendship that I first wrote back in 2014. I’ve also written a book about us, have been working on that book over years and years of time…and recently signed a contract with Elk Lake Publishing to publish it. More on that to follow. For now, the post.

***

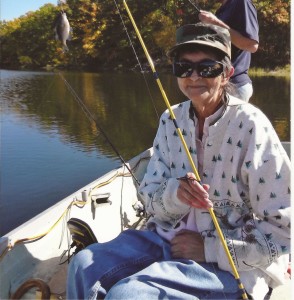

On a foggy morning one early March, I met a tiny woman encased in a puffy tan coat. She had black hair with a fur cap perched on top of it, the hair cut short except for a thin trail that hung down her back like a wimpy garter snake. The planes of her face were flat, with the folded and refolded look of a crumpled paper bag. Her eyes were dark, the folds of skin at their corners giving them a slanted appearance.

I loved this woman from the first moment I saw her: the tiny, intense perfection of her, the way her glasses sat sharp and clean on her face, the bright look of her eyes, and the way all her wrinkles massed upward when she smiled. Her name was Charlene. At that time, I drove for a company called Indianhead Transit and had been assigned to take Charlene to her dialysis appointment. I helped her to my car, my steps excruciatingly slow to match hers, got into the driver’s seat, and backed the car out into the foggy darkness of the road. “The Ojibwa have a saying about the fog,” she said. “They say, ‘The Creator sent the clouds to earth.’”

We talked a lot about God that first dialysis trip. “I am amazed at how He made everything on earth round,” she said. “The leaves are round, the drops of water are round, the scales on a fish are round, and even the little blades of grass, when they first come up, are curled into a ball. It just makes me love Him so much.” There was wonder in her voice, joy in her eyes.

I asked her if she believed in Jesus. She considered a moment. “Yes, the Ojibwa have taken the Creator’s Son, Jesus.” But when I mentioned the Bible, she was adamant in her disbelief. “The Bible is just a white man’s book!”

I wondered how she could believe in Jesus while not believing in the Book that told about Him. The woman was a study in contrasts.

She would coo at her little dog in the sappiest, drippiest form of baby talk possible, and fifteen minutes later when the dog displeased her, would yell so harshly it would streak for its crate, Char’s hand raised threateningly behind it.

When a gunner mowed down twenty kindergartners in Newton, Connecticut, Char had a solution. “They should take that man and strip him naked and make him run across that field and back. If he survived, he could live, and if he didn’t, we’d be rid of him.” It was winter, snow deep on the ground, temperatures below zero. I imagined the scene, the people gathered on a field edge watching a naked man run, waiting to see if he would fall, jeering maybe, scorning his naked body–it seemed gruesome, primitive, harsh. I thought her unmerciful. And yet, she told me that the only time she went hunting she had the opportunity to shoot a beautiful buck, and she couldn’t bring herself to do it.

She was the sharpest, meanest little lady I ever knew.

She was the person I went to for comfort when my uncle died.

Not too long after we became friends, we went together to the annual powwow up on the rez. During the drive home, Char brought up blacks. “I just don’t like ’em,” she said, looking at me to see how I would react.

“Why?”

She shrugged. “I just don’t. They live on welfare, and they don’t get married, and they pop out all kinds of niglets that the grandmas have to take care of, because the moms don’t.”

“All your relatives on the reservation take money from the government,” I pointed out. “And you have unmarried nieces who have children, and the grandmas help take care of them.”

She nodded. “That’s true. But I still don’t like ’em.”

The unreasonableness of it angered me. I had dark thoughts about the hidden evil of the human heart. “Well, then you’re directly disobeying God’s command. The Bible says, ‘Love one another,’ and ‘He who loves God loves his brother also.’ When you die and stand before God, if you’re in direct disobedience to Him, how do you expect that He will let you into heaven?”

Charlene looked pleased, her face smiling inside itself. Probably because she had never before seen me vehement. “Well, I don’t care if it is going against God’s command,” she said, after a pause. “I just don’t like ’em.”

I held her racism against her until election time rolled around and she voted for Obama.

By that time, I realized that with Char, you had two choices: you could let her drive you mad, or you could accept her.

I chose to accept.

We disagreed on almost everything. There were three things that drew us together. The first was that she was lonely and needed a friend. The second was that I needed to be needed; I was looking for someone to help. And the third–the third was the hardest to pinpoint. It was a sort of primitive and driving hunger for God we mutually shared and mutually understood.

She leaned across a table one day, her eyes dark and unfathomable. “I’m reading the Bible,” she told me. “And, Luci, I don’t know why.”

I had given her the Bible. It sat on her table for weeks, in the exact same position every time I visited. I had thought she never touched it. Turned out she was reading three chapters a day.

Our friendship was stormy, but always intense. At times I felt overwhelmed by her. I wrote a poem for her once, to try to make her understand how it would feel to be me, one small gap between an old woman and her loneliness. To try, maybe, to gain a little breathing room in a time when I sorely needed it and didn’t know how to take it.

This is the poem I wrote, and it is with this poem I end what I will tell, for now, of the tender and contentious little woman who was Charlene, my friend.

For Charlene, who lived on this earth from October 28, 1941 – February 23, 2013

I MET AN OLD LADY

I met an old lady

wrists fine as bone china

her eyes black

and her hair black

as crow’s wing

but her heart was red.

One day her heart dropped out

and fell into my fingers.

I did not know what to do with it.

I had never had a heart.

I cradled it in my two hands

fingers light

against its throbbing

careful

not to bruise it.

***

Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

I love this, Luci!! Your writing is so detailed and easy to follow that I always feel like I’m right there with you!.

I pray your hearts, dreams, and expectations are continuing to heal. I don’t share that experience with you but I am truly sorry for the loss of your precious baby.

I can’t wait to read your book!